|

On The Eve Of Battle

Americans Are Choosing Not Between Two Candidates, But Two Postliberal Regimes

|

Well, here we are on Election Eve. I guess everybody has his or her mind made up by now, and all that’s left to us is to vote, then wait and see. I wish I were back home for this. Not sure why. I might try to find an election-watching party over here, but the results are going to be very late in coming in, on Budapest time, so I might just stay home. If Trump wins, I want to be with other people, celebrating. If he loses, it’ll be best to stay home. I do think he’s going to win, though.

For me, this is not a vote between two (highly flawed) candidates, but between two ways of governing. I have an essay coming out in The European Conservative later today about this, so I don’t want to give too much away here. The core of my argument, though, can be found in this must-read essay by Nathan Pinkoski, in First Things.

In it, Pinkoski argues that classical liberalism in America is a thing of the past, and we are actually living between versions of postliberalism. What does he mean by that? Excerpt:

Twentieth-century civilization has collapsed. It rested on an essential tenet of liberalism: the state-society, public-private distinction. The state-society distinction reached its apogee in the mid-twentieth century, when the triumph and challenges of the postwar moment clarified the importance of defending social freedom from state power, while ensuring that the public realm was not taken over by private interests. Over the last few decades, this distinction has been eroded and finally abandoned altogether. Like it or not, the West is now postliberal.

This is not the same “postliberalism” that we are accustomed to hearing about. Postliberal thinkers from Patrick Deneen to Adrian Pabst have exposed the conceptual problems inherent in liberal theory. Liberals justify the separation of the public realm from the private sphere by appealing to value neutrality. This notion of separation involves a certain moral and metaphysical thinness. The commitment to neutrality is thought to prevent states’ coercing belief through law and force. It protects the private sphere, so that individuals and associations can live out their creeds. Yet by promoting civic neutrality, liberalism socializes us to moderate our ambitions for public life. Against this view, postliberal thinkers argue that the liberal state’s rejection of a substantive vision of the good hollows out politics and civil society. Liberalism produces a state bent on driving tradition and religion out of public life, an atomistic society in which money is the only universally acknowledged good. Postliberal intellectuals contend that if our ruling classes relinquished their liberal commitment to neutral institutions in favor of a substantive vision of the good, we could renew our civilization.

The Brexit referendum and Trump’s election in 2016 revealed the extent of the West’s malaise. Eight years ago, the postliberal critique seemed exciting and relevant, even as liberal intellectuals mounted impressive counterattacks. But these disputations have little to do with how we are actually governed. Governments long ago breached the barrier separating the public and private realms. Nor is the state the only danger, for the supposedly liberal institutions of civil society have given up on neutrality. Cancel culture is corporate and academic culture. The financial and tech giants pry into the private lives of citizens and punish them for their words and deeds. For quite some time, a substantive vision of the good has already been ruling over both state and society.

He goes on to argue that after 1989, in the West, the state expanded its power through ideological capture of the ruling class, which acts more or less in unison, within private institutions to achieve its goals. This is not only something that came about through Democratic administrations. The George W. Bush administration expanded the reach of the state after 9/11. The United States, under successive governments, has weaponized liberal institutions of international governance to make them serve American goals. Covid exacerbated and clarified this, as did the George Floyd aftermath, as has the transgender issue, with the state and its ideological allies in business and private institutions using civil rights laws and concepts to force illiberal concepts of race and sex on unwilling populations, who were not given a say in the matter.

The British commentator Ed West expands on this in his latest Substack essay. (I’m not sure if this is paywalled or not, but oh boy, you should subscribe to Ed’s consistently excellent Substack, which focuses mostly on history and the way it impacts us today). Excerpt:

The number one reason that people give for voting Kamala Harris is ‘the future of democracy’. Yet Republicans have reason to fear the other side, too, that progressive rule will further embed a system where decisions are taken away from elected politicians and steered by a network of NGOs, activist judges and bureaucrats schooled in monocultural left-leaning institutions, where freedom of speech is crushed and a demoralised, impoverished population is led by a ruling class who despises them and their history. A bit like Britain, in other words.

There is also the issue of immigration, which on a large scale makes democracy more fragile. The experience of the United States is different to Europe, since the former has indeed always been a ‘nation of immigrants’. Yet until 1965, the US was in essence still a European country with a small, partially disenfranchised African-descended minority in its poorer, less populous south. Even Americans of southern and eastern European descent were under immense social pressure to conform to an Anglo norm.

Columbus Day, now a symbolic source of division, was once designed to celebrate, and integrate, Italians in America, the largest groups of Ellis Island immigrants who joined a country that until then had been dominated by north-west European Protestants. That they did successfully integrate was in part due to the fact that large-scale immigration was paused from 1924 to 1965, a political impossibility in today’s America.

America is now something different, what Barack Obama called a country founded on an idea - but might also be described as a ‘progressive caliphate’, a country defined not by ancestry but belief. This is a fine ideal, but it is a novelty for a democracy, and where this kind of society has existed in the past it has always been ruled by autocrats who enforced the state religion with an iron fist.

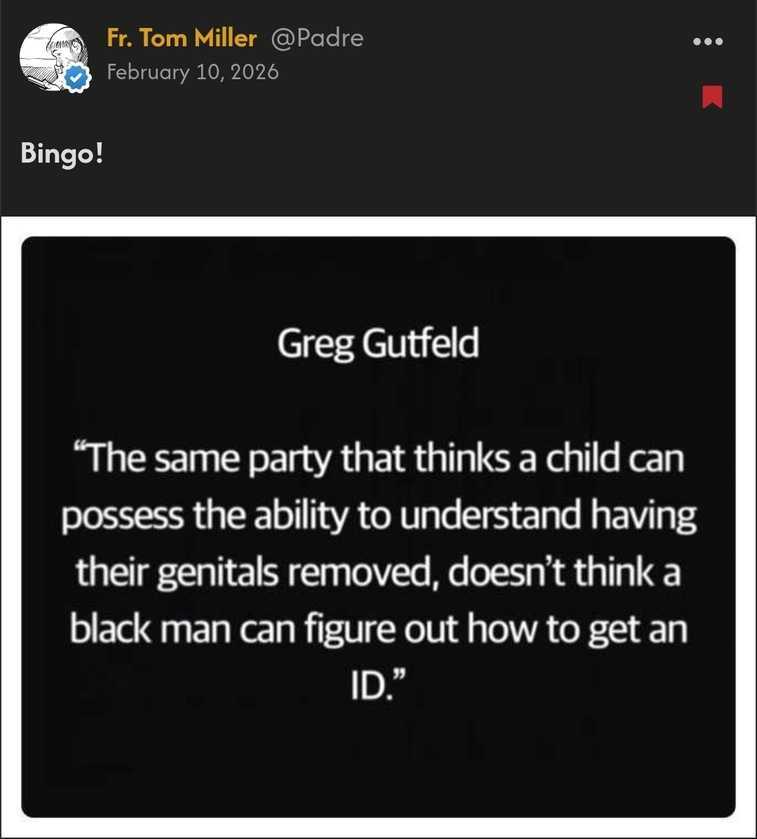

Democracy and diversity make unusual bedfellows. Across the world, where a previously secure majority group has begun to lose its numerical advantage, it has led to conflict, most notably in Lebanon, Northern Ireland and Fiji. Multi-ethnic democracies are fraught, because elections are a tribal headcount, and made less legitimate when one side appears to be recruiting more of its followers. The issue of Voter ID is related to how conservatives feel that the Left is cheating the system by importing voters, with some justification.

In these quasi-democracies, political representatives use the system to hand out rewards to their side, Kamala Harris’s recent proposal of $20,000 loans for black men being typical of countries where politicians use the levers of power to take from unpopular market-dominant groups. Unlike in the United States of the 1960s, there is no need to frame these arguments through a sense of shared Christian pity - it’s a far older and less revolutionary instinct.

Diversity is only one cause of polarisation, and not a precondition: Poland is one of the most polarised countries in Europe and one of its least diverse, while homogenous South Korea is the most divided of all – by sex, more than anything.

Neither are these uniquely American trends, with many of the same patterns also found in Europe: the ‘great realignment’ is now a British phenomenon, too, and indeed was the core story of Brexit. That referendum saw British politics grow far more polarised, with Leave and Remain identities becoming far stronger than party affiliations. While that issue has subsided, for now, voters have instead become polarised over immigration.

Whether we follow a similar path to the United States will depend on many things, including whether trust in institutions continues to fall and immigration levels remain high. The extent to which any politician can change the nature of voting coalitions is also limited: when a country has a populace so divided over core issues, parties will simply come to represent those interests, although individuals can set the tone.

Pinkoski and West are elaborating on the basic point I made in Live Not By Lies: that we are living in a kind of “soft totalitarianism.” To restate the point: hard totalitarianism is the Soviet model (or the Chinese model), in which all power resides in the state, which enforces its ideology through violence, or the threat of it. Soft totalitarianism, by contrast, is when a single ideology rules a society without significant state coercion, because the class that rules institutions of private life (the professions, the universities, the media, and so forth) presses its ideology onto the body politic. A second quality of soft totalitarianism is that it does so often for “therapeutic” reasons, e.g., to protect those it conceives as victims from the depredations of the deplorable masses, even to the point of shielding the “oppressed” from having their feelings hurt.

When one is not permitted to say that a person who is a biological male is a man, without facing serious penalties — say, the law student who faces expulsion for “aggressive pointing” at a transgender advocate — you can say we live under soft totalitarianism. Or at least, under left-wing illiberalism.

The Left doesn’t see this, of course. They think they are “defending democracy.” Last week, The New York Times, a leading institution of left-wing illiberalism, published an essay by two government professors at Harvard, another such institution, arguing that in the event of a Trump victory at the polls, the ruling class should institute a color revolution to deny Trump the opportunity to govern. Thus, they argue that we must destroy democracy to save it.

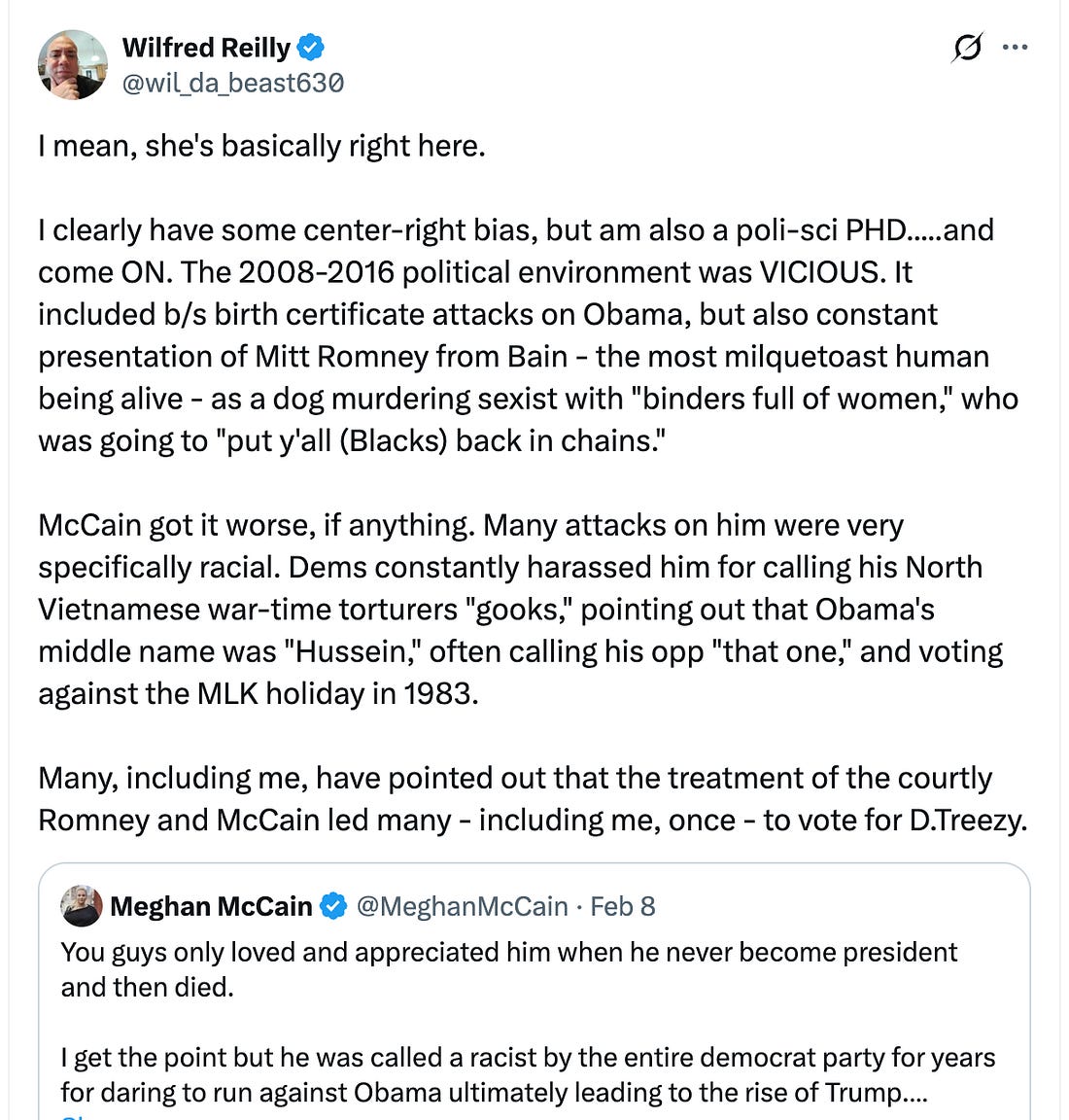

Whatever this is, it’s not liberalism. In fact, as a Times subscriber, I’m struck by how propagandistic the newspaper has been in this campaign. If you only got your news and information from the Times, you would have no real idea about the country you live in. The paper has been so hysterically anti-Trump that unless you read Ross Douthat — a conservative who is deeply skeptical of Trump, but who at least makes a serious effort to understand and explain why so many Americans support him (great piece here, ungated) — you would think that half the country was in the grips of authoritarian madness. In the pages of the Times, as in all of the legacy media, there has been virtually no attempt to understand the failures of the Left, and why so many Americans have no trust in them, or more broadly in American institutions.

The fact that the Democrats, having despised Dick Cheney and his warmongering for over two decades, have allied with him and his equally hawkish daughter Liz, tells you everything you need to know about why Pinkoski is right, and we are facing a choice between regimes — and that the line between them does not run strictly between Democrats and Republicans.

As you know, I don’t have much faith that a Trump restoration will turn the tide. But maybe I’m wrong; I was wrong about him in 2016, and he was a better president than I expected. But I wholeheartedly hope he wins this time, as a democratic repudiation of the governing regime. If Trump wins, I do hope and expect that he will be more aggressive this time in pushing back against the Left and its hegemony over the institutions of American life. What I learned from living in Hungary and observing Viktor Orban is that the only effective way to fight back against these illiberal left-wing powers is to refuse their manipulative lies.

On the other hand, Hungary is a deeply divided country, over politics. So too is America, and the election, whoever wins, won’t fix this. God only knows what will happen to our beloved country. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre understood what had happened to us across the West in his early 1980s book After Virtue. Though he was not a Christian when he wrote the book (he later converted to Catholicism), MacIntyre knew we had lost the ground of our common values — Christianity — and the Enlightenment gave us no universal framework within which to anchor our reason. The age of liberal democracy depended on residual Christianity to work; now that that has gone, we find ourselves at odds over what it means to live a good life, in community.

Take a look at this four-minute clip from Joe Rogan’s interview with Sen. John Fetterman:

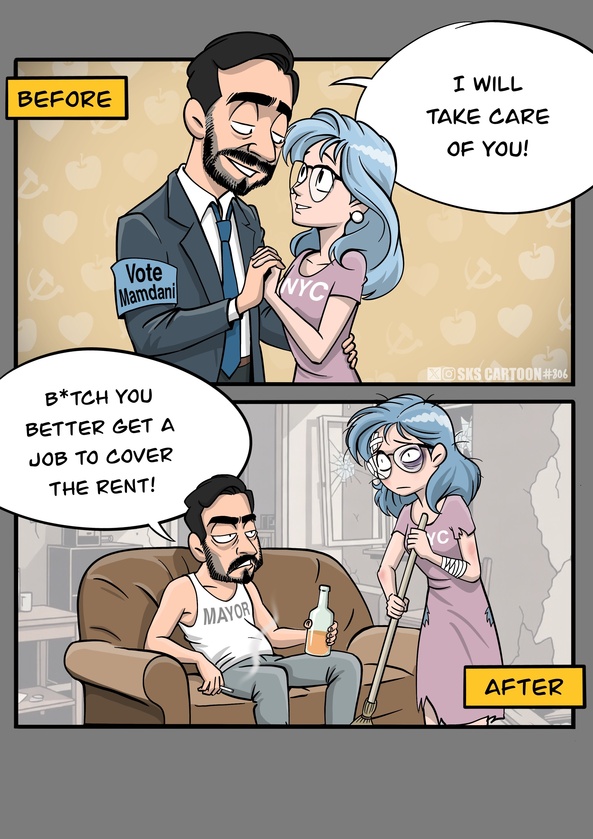

What Rogan is pointing out here is that he pressed Fetterman on what it means that the Biden administration permitted millions of illegal migrants to settle in swing states. It looks like they are importing voters from abroad to cement their power. Fetterman squirms, but doesn’t deny it! Look, I live in Europe, and you can see in countries like France and Germany that the alliance between the left-wing parties, who hate their civilization and think it is nothing but a story of oppression and racism, have formed a political bond with Islamic migrants, to dispossess the ordinary people of those countries. This is what Renaud Camus means by “the Great Replacement.”

It is not as bad in America as it is here, because at least the Latin American migrants share a Christian background, which makes them more compatible with American mores. Still, it is a scandal that political parties would try to dissolve the American electorate by importing foreigners who will likely vote for them. The American people, of all races, were not given a choice here. In Europe, the only national leader who has consistently refused this is … Viktor Orban. That horrible fascist, if you believe the media, academia, and the US Government. But coming to Hungary to visit, and indeed to live here, tells a very different story. It tells you that we have been lied to, not only about him, but about what our ruling class is really about. It’s not liberal democracy, I can tell you that.

Whatever happens tomorrow, I am grateful for you all, even you Kamala-voting libs! We are all in this together, somehow. Let us meditate on the tragic sense of Lincoln’s words in his second inaugural address, delivered near the end of the Civil War: “The prayers of both [sides] could not be answered—that of neither has been answered fully.” Yet America endured. I think it still can.

We Are Being Played

Here’s a must-read bit by the UK commentator Matt Goodwin, about the way the British government and the media managed public reaction to the stabbing deaths in Southport of three little girls by a young black man, the son of migrants. Goodwin begins by making a broad point about how the ruling class will not allow discussion of the deleterious effects of mass migration. Excerpts:

Wondering if a mass influx of millions of low-skill migrants might be one reason why our economy and public services are deteriorating, and why Chancellor Rachel Reeves was just forced to impose record rates of tax and borrowing?

“Oh, you’re misinformed!”, they cry in unison, while at the same time concealing information about the cost of our asylum system in the welfare budget and refusing to share information about tax and welfare by nationality and immigration status.

It is, put simply, outrageous and is something I will not stop talking about until all of this information is made available to the hardworking, tax-paying British people.

And nowhere has this trick been more visible than in the response of our hapless elite class to the horrific atrocities that were committed in Southport, where three precious little girls –Elsie Dot Stancombe, Bebe King, and Alice Da Silva Aguiar--were brutally murdered at a dance class, while many more were nearly stabbed to death.

More:

Once again, those who asked questions were instantly warned about “misinformation” while actual information about the suspect was suppressed or downplayed.

Interestingly, the few details that were initially released appeared to be ones designed to calm tension, telling people the accused was “Cardiff-born” and his parents were “a lovely couple”, which I’d suggest simply made little sense to most people.

Into this vacuum then arrived all the usual stories about “solidarity” and communities “coming together”, much like what followed the bombing of our children at the Manchester Evening News Arena by “British” citizen Salman Abedi, or the horrific murder of Sir David Amess MP by “British” citizen Ali Harbi Ali.

All of this, too, was rapidly contrasted with stark warnings about the “far right”, which has not been a serious force in this country for years, to essentially warn people off asking deeper questions about what is going on in our country.

A small minority who were unable to control their anger and rage rioted and were, rightly, sent to jail. But so too were many people who, often writing online in their own homes, drew a line from the atrocity in Southport to immigration and Islam.

… People from the left-leaning elite class, meanwhile, who had previously taken only minutes to brand past attacks as “far-right terrorism” suddenly urged caution and delay, while quickly moving the discussion on to debates about how best to clamp down on free speech and free expression in our country.

Well, well, well:

Now we know that the Southport attack does have something to do with these very issues. I don’t know if it’s the discovery, this week, that the son of Rwandan immigrants tried to make the deadly biological weapon ricin or that he downloaded an al-Qaeda training manual for Islamist terrorists titled ‘Military Studies in the Jihad Against Tyrants’, which offers advice on urban warfare, terrorist tactics, and how to establish terrorist cells, that has left me thinking we might not have been given the full story about this ‘Welshman’.

Furthermore, I’d hazard a guess that many people in the corridors of power have known a lot more about this story than they’ve been letting on. As anybody who has worked in Number 10 knows, as Dominic Cummings pointed out this week, despite what we’re being told, despite all the talk about “misinformation” or “disinformation”, it is in fact highly likely that Keir Starmer, Yvette Cooper, and the authorities would have known almost immediately about this information.

You cannot trust these people, anywhere — except to lie and manipulate in the service of their preferred lies. We have the same thing in America, of course. Last bit from Goodwin:

Sorry, but do they actually think we are this stupid? Do they actually think we will just blindly follow the officially approved narrative? Do they not think the Mums, Dads, and concerned citizens of this country will relentlessly pursue the truth and hold our rulers to account? Do they really just think we will shut up and go away?

Not. A. Chance.

Here's what I think. I think they think we are stupid. I think they think we will forget about the scandal in Southport and move on with our lives. I think they think we will be cowed into silence or duped once again by the same misinformation trick, that we will scuttle off and not dare ask questions about what is happening to our country.

But we won’t.

Live not by lies! One major reason the lies flourish is that the ruling class makes it too painful to speak the truth. Another reason is that many people — perhaps most people — can’t bear to face up to the hideous realities of what we have become, and what we are facing. But face it we must. If we don’t, we’re over. This is not an abstract threat. This is real life. I had lunch on Friday with an Irishman furious over what migration has done to his village. The Irish government has imported and settled more Ukrainian migrants there than the population of the actual village! To say it has disrupted life is to badly understate the reality. These are not Africans, but Ukrainians, but the point is they are not Irishmen! The people of this small rural village have been forced to deal with something they are not prepared for, could not possibly be prepared for, and which is changing their settled life forever.

And they were not given a choice in the matter! They are paying the price for the moral vanity of Ireland’s ruling class. So, too, are Americans in similar circumstances. Look at this news last week from small-town Ohio:

The mayor of a small village near Cincinnati says he needs help from the federal government after a surge of illegal immigration primarily from Mauritania that nearly exceeds the local population and that he says is "unsustainable."

"Our county officials estimate that we have around 3,000 of those that have come to a village of 3,420 residents. And our complaint is, if the federal government is going to have an open borders policy, with that they need to have a policy directing these immigrants to communities that can absorb that kind of population increase," Lockland Mayor Mark Mason told Fox News Digital.

Democracy depends on the consent of the governed. And yet we are told by The New York Times, Harvard professors, and their kind that to be angry about all this only shows that we are threats to democracy.

We aren’t threats to democracy. We are threats to them. I hope they are frightened.

The Gender Gap, Explained

Mary Eberstadt considers the yawning gender gap in US politics. Excerpt:

The mystery isn’t that many of today’s young men are deserting the side that loathes them and fears them and sometimes longs to queer them. It’s that socially and economically superior players haven’t a clue anymore about what makes young men tick—whether it’s driving fast, failing to ask strangers for directions, treating Sunday football like church, or saving a subway car full of strangers from disaster. From Democratic politics to Hollywood, from prestige quads to the C-suite, those players haven’t only lost the script about young men. They’ve unlearned the alphabet of human nature.

There is something unique called male self-respect. It’s grounded in the belief that rules exist and retain their authority, from baseball to church to war, no matter how many times they’re broken. Forgetting that fact of nature renders progressivism and its fellow-travelers incapable of understanding a major chunk of the electorate. The real mystery in the political sex imbalance isn’t about boys and men, but girls and women. It’s why so many obediently keep trotting in the same lanes marked out for them since the 1960s, pelted with the same messages that have been making life miserable for decades now—men are bad; the future is feminine; career first, egg-freezing next; the best ending after falling for someone and making a baby together is to get rid of it.

White progressives are scandalized that not everybody hates themselves as much as they do.

Queering The Donbass (And Everywhere Else)

I coined the phrase “queering the Donbass” to mock the US Government’s desire to remake the world in the image of progressive America, whether or not it is in our country’s national interest. Now Christopher Rufo has produced a report on how the US State Department has made advocating for LGBT rights an essential part of American foreign policy Excerpt:

The diversity agenda has been translated to the day-to-day operations at embassies around the world. Some embassies are even screening security positions for adherence to DEI. In a job posting for a security escort position at the U.S. Consulate General in Lagos, for example, applicants are told that “[t]he U.S. Mission in Nigeria supports Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility (DEIA),” and that “[a]ll genders are welcome to apply.” Some two-thirds of the job summary is dedicated to DEI, as if U.S. security officers should be more concerned with gender pronouns than terrorist attacks.

Inside the embassies, gender has become a near obsession. State’s latest annual LGBTQI+ progress report lists countless present and future efforts across all foreign agencies to make the world safe for queer theory, from “Pride Events at Headquarters” to “Gender Equity in the Mexican Workplace.” Among these is a department-wide partnership with the Global Equality Fund, a public-private entity “dedicated to advancing and defending the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons around the world” that has directed funds to 116 “grassroots” LGBTQI+ organizations in 73 countries.

State itself asserts that U.S. diplomatic efforts should reflect progressive ideology. In a special report on “DEIA Promotion” by the department’s advisory commission on public diplomacy, State evaluates “how U.S. missions adapt existing programs to DEIA principles,” which are to inform “all aspects of the Department’s policymaking as well as efforts to address barriers to opportunity for individuals historically and currently burdened by inequality and systemic discrimination.” Realpolitik, in other words, should give way to critical theory.

These efforts raise a critical question: Does gender theory advance the U.S.’s national interests? The answer appears to be no. But that is hardly an obstacle for State’s gender activists. They want to hang the rainbow flag throughout the benighted parts of the world. This mission trumps all others.

What on earth does any of this have to do with advancing American national interests abroad? It’s cultural imperialism, straight up. This is part of the reason why more and more people abroad hate us.

Bach In Autumn

Let’s pivot to something happier, shall we? Autumn is my favorite season, and nothing musically says autumn to me like Bach’s Suites for solo cello. Here is the introduction to them, by the man who plays my favorite version, Yo-Yo Ma:

Bourdain In Lyon

I discovered over the weekend that one of my all-time favorite hours of television, Anthony Bourdain’s episode of his visit to Lyon, France’s gastronomic capital, is available on YouTube:

At the 16:00 mark, Bourdain and Bill Buford dine at Café Comptoir Abel, the city’s oldest bistro, where Bourdain tastes a classic Lyonnaise dish: quenelles, a dish made of filleted river pike inside a soft dumpling, coated in a sauce of béchamel made with crawfish butter. Because of the Bourdain episode, I visited Lyon in 2015 with friends, including the incomparable James C. We made our way to Café Comptoir Abel, and I ordered the quenelles. James C. captured the very moment I tasted what was one of the best meals of my life:

They really are that good!