This Minneapolis shooting turns out to be much darker than I realized yesterday, when I first wrote. The killer was quite clearly possessed, I think. I mean that literally. This story from the New York Post details some of his chaotic, anti-Semitic, hateful beliefs, which seem to have no ideological core. His transgenderism seems to have been not so much at the core of his identity, but rather one manifestation of a malignant, radically disordered mind. Here is the 11-minute video he left behind, before the shooting. It is a horrifying glimpse into the mind of a madman.

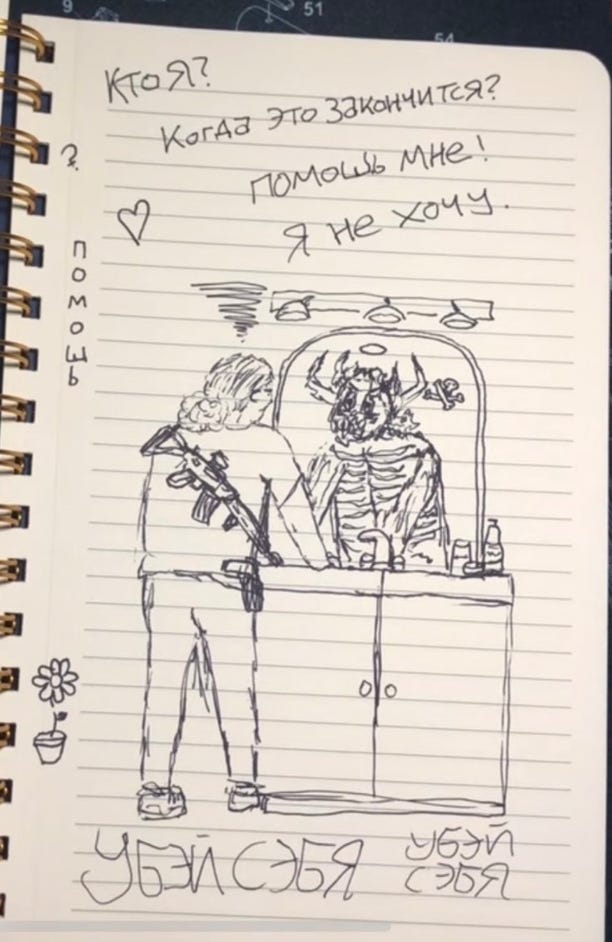

This page from his journal jumped out at me when I saw it yesterday:

The Russian says:

Again: possessed.

Let’s not forget the valorization of revenge violence among trannies. Watch this. And look at this:

Peter Savodnik takes the measure of this lunatic. He goes through the various “explanations” people have offered, in an attempt to make sense of Westman’s heinous act, and concludes:

All that finger-pointing obscures a deeper point: Westman seems to have been driven by an all-consuming, destructive force, a nihilism—the conviction that life is meaningless; that words like truth, justice and God are empty slogans; that everything must be razed.

Nihilism is not some obscure academic notion. It stretches back to the 19th century—early Russian radicals were called nihilists—and it has waxed and waned across the past 150 years. Today, you can feel the nihilist impulse coursing through America, which has been mostly stripped of its faith and a shared national culture and has seen once-great institutions—universities, corporations, churches, nonprofit organizations, the media, the military—become engulfed in scandal and politicization.

It is an understatement to say America is struggling to infuse young Americans with a sense of purpose.

Earlier this year, the FBI introduced a new category of criminal: the Nihilistic Violent Extremist, or NVE.

If jihadis kill for Allah, and anti-government extremists like Timothy McVeigh killed in the name of some demented notion of freedom, then NVEs kill simply because they want to kill. They don’t have much in the way of ideological commitments—as the confusing hodgepodge of aphorisms Westman scrawled into his rifle, pistol, and shotgun makes clear—beyond a commitment to chaos and evil themselves.

If we are dealing with true nihilism, then we are all in for a hell of a ride. There’s no way to counter people who want to murder and cause havoc simply for the pleasure of doing it. Last week at the Midwestuary, I heard lots of talk about the spread of nihilism among young American males. This is the far fringe of victims of the Meaning Crisis. Max Remington texted me overnight:

America's Years of Lead are going to be driven by this kind of nihilistic violence by people of all ages. America has so many lone wolves, I wouldn't rule out the possibility it could collapse the country, honestly.

I don’t know the extent of this problem in the US, nor do I know if Europe has a similar problem. But see, this is the kind of thing that David Betz is talking about when he raises the prospect of “civil war”. It will almost certainly not be anything well-organized, he says, but rather random acts of killing, violence, and sundry mayhem, committed by people with different motives, or no motive at all other than destroying a society that they believe has failed them.

The great contemporary literary critic Gary Saul Morson explains the nature of 19th century Russian nihilism, which is not the same thing as what Robin Westman might have instantiated. Excerpt:

“Nihilist” and “nihilism”—terms typically attributed to novelist Ivan Turgenev—originally referred to a group that arose in Russia around 1860. Today we often call people nihilistic if they extend no hope that conditions can improve. Unqualified pessimists, they regard all grounds for optimism as illusory. We also use the term “nihilism” to describe extreme relativism about the bases of human knowledge. Science, in this view, is just another ideology, based, like all ideologies, on the interests of a ruling class. Accepted knowledge is nothing more than power made into a philosophy justifying it. This kind of nihilism often interprets various philosophers—Hume, Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, Feyerabend, and others—as justifying the claim that one can build on no certain “foundations.”

Neither understanding of nihilism applies to the original Russian nihilists. Far from despairing, they believed that they knew just how to build the perfect society, which, they also held, could be realized in a few years. Regarding “science” as a set of infallible (and mostly metaphysical) dogmas, they deemed their favored social theories scientific and therefore utterly beyond doubt. As their critics observed, these science worshippers missed the whole point of science, openness to contrary evidence.

The group’s leader, Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-1889), exercised immense influence. His utopian fiction, What Is to Be Done? (1863)—the question was anything but rhetorical—became the most widely read book among the intelligentsia before the Revolution. Lenin credited it with making him a revolutionary, and the Soviets hailed Chernyshevsky as a thinker in the same league as Marx and Engels. Tolstoy, on the other hand, referred to him as “that gentleman who stinks of bedbugs,” a loathsome figure who has persuaded his followers that “to be outraged, bilious, and spiteful is a commendable thing.”

In his novel Demons (sometimes translated in English as The Possessed), Dostoevsky illustrates and condemns the nihilism popular among young people of his era. His character Verkhovensky is a political nihilist, aiming to disrupt society for the sake of creating a utopian future. By contrast, Stavrogin is an existential nihilist, who truly believes life has no meaning, and who lives to channel his despair into destruction.

I have this sense that we are living in a culture accelerating towards a general calamity. Recall that when an audience member in a screening of Live Not By Lies asked me earlier this year if I thought the threat of soft totalitarianism was waning because Trump is in power, and pushing back on woke, I said no. All the conditions that Arendt identified as conducive to totalitarianism are still very much with us: mass loneliness and alienation, a loss of faith in institutions and hierarchies, a love of transgression for its own sake, a willingness to believe that “truth” is whatever satisfies one’s desires, and so forth.

We know very well where wokeness take us. I am particularly aware of how wokeness validated racial identity, and privileging racial identity. The right-wing version is now emerging ferociously. The very right-wing demons I warned many years ago that wokeness was summoning are now here. God only knows how this ends. I’ve always had a superstitious belief that the Jews are a canary in the coal mine of society: that anti-Semitism is a sure sign that a society is giving itself over to radical evil. Now we see that rising on both the Left and the Right.

Last night in Rome I was at a social event with some people from all over Europe. A couple of British interlocutors expressed extreme worry for their country. There’s the migrant crisis, of course, but also the economic crisis, about which I knew little. They talked about how the cost of living is becoming unsustainable, and how the government is barreling towards a fiscal Armageddon. Last week, the Telegraph reported that the government might be forced to appeal to the International Monetary Fund for a bailout. If that happens, my British interlocutors said, there’s a very good chance that the IMF simply will not have the funds to cover Britain’s debts. And if it does, the IMF will demand radical reforms, including either the slashing of pensions, the gutting of the National Health Service, or both. These are moves that the Labour government cannot politically do. So … what, then?

Britain is a post-Christian society. What holds it together, and prevents it from descending into chaos and violence should the economy collapse, particularly at a time of increasing racial and religious tension?

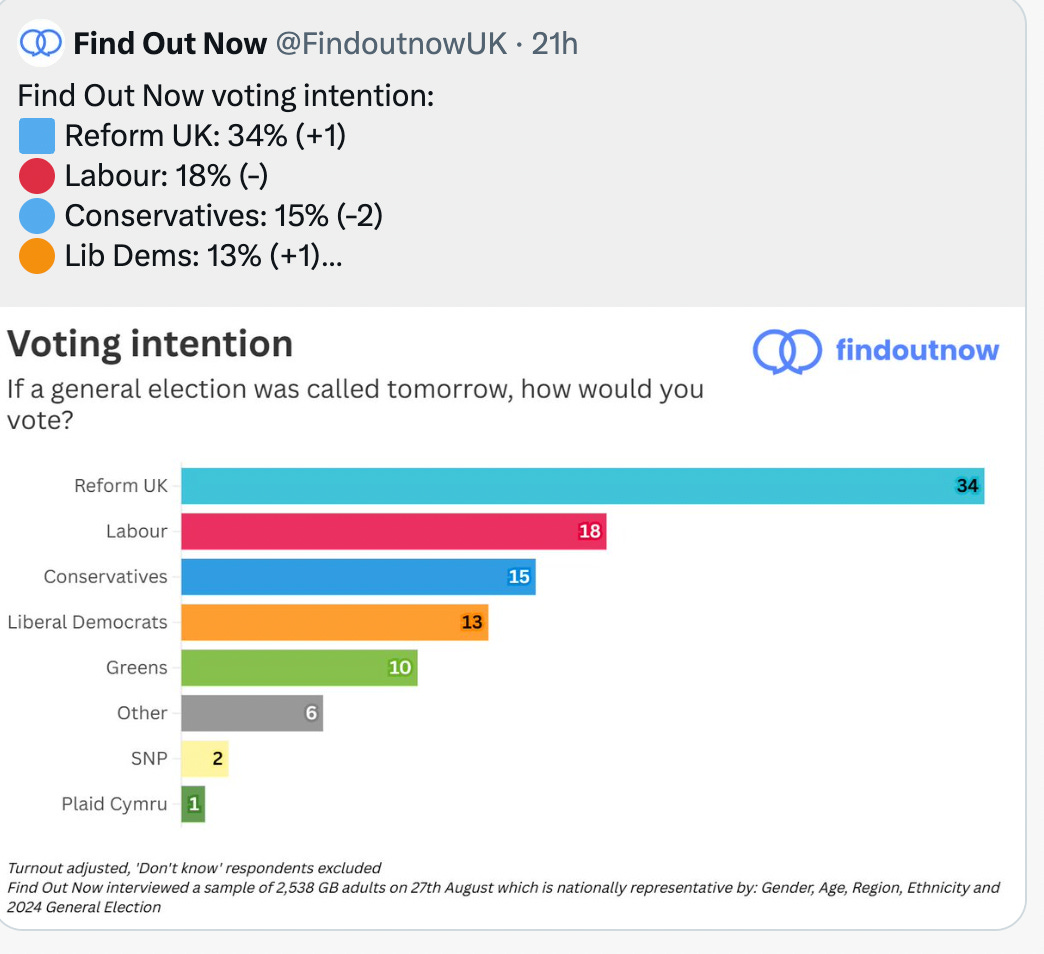

Notice that after Nigel Farage’s deportation speech, Reform has surged in popularity to the point that it has more support than the Tories and Labour combined! Has that kind of thing ever happened?

What if the same fiscal disaster happens to France, which is facing its own fast-approaching day of fiscal reckoning? Francois Bayrou, the prime minister, will have to resign in the days to come over the budget impasse. He appeared on French TV this week to say bluntly that the core problem is the Boomers’ pensions, which are politically untouchable.

I also talked to a German woman, who said that her own country is headed towards fiscal disaster. She told me that she used to fear and loathe the AfD (Alternative For Germany), but after seeing how extreme the German establishment has been in trying to crush the AfD, she now sympathizes with them. A German man earlier in the evening told me the same thing.

A German court has banned an AfD candidate for running for mayor in a German city. You’ll never guess why:

The exclusion began when incumbent Mayor Jutta Steinruck (formerly SPD) contacted the SPD-controlled Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of Interior, requesting information about AfD candidate Joachim Paul from the Office for the Protection of the Constitution. The SPD-led ministry had already made headlines by announcing that civil servants expressing sympathy for the AfD would be excluded from state positions.

The resulting 11-page report claimed “good reasons to doubt Paul’s loyalty to the constitution,” citing:

A photograph: Paul posted an Instagram photo of himself with Austrian activist Martin Sellner, who was banned from Germany for advocating the deportation of migrants, including those with citizenship who fail to “sufficiently assimilate.”

The concept of “remigration”: Paul gave a November 2023 lecture titled “Immigration: A Matter of Destiny—Why Remigration is Necessary and Feasible.”

Literary references: A 2022 article by Paul in the Austrian magazine Freilich referenced Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, stating, “Tolkien’s entire work reflects a conservative mindset of particular value to contemporary conservatism … The protagonists fight for a cause greater than themselves: their homeland, the survival of their culture, a just order, the defense against a global threat.”

Cultural interests: Paul’s appreciation for Wagner’s Nibelungenlied, which the report claims holds significance for him in terms of “national pride.” The report notes he offers video seminars on the medieval epic.

For Germany’s liberal and cultural left, all of this undoubtedly smacks of “Nazi.” But in a democracy, the question of what to make of Paul’s ideas and associations should have been left to the public. Paul might not have won—some polls didn’t favor him despite the AfD’s strong February performance in the region, where it came a very narrow first with 24.3%. But the establishment wanted to take no risks, knowing full well they have lost the public struggle on migration and national values.

The dude likes Tolkien and Wagner. Clearly a Nazi!

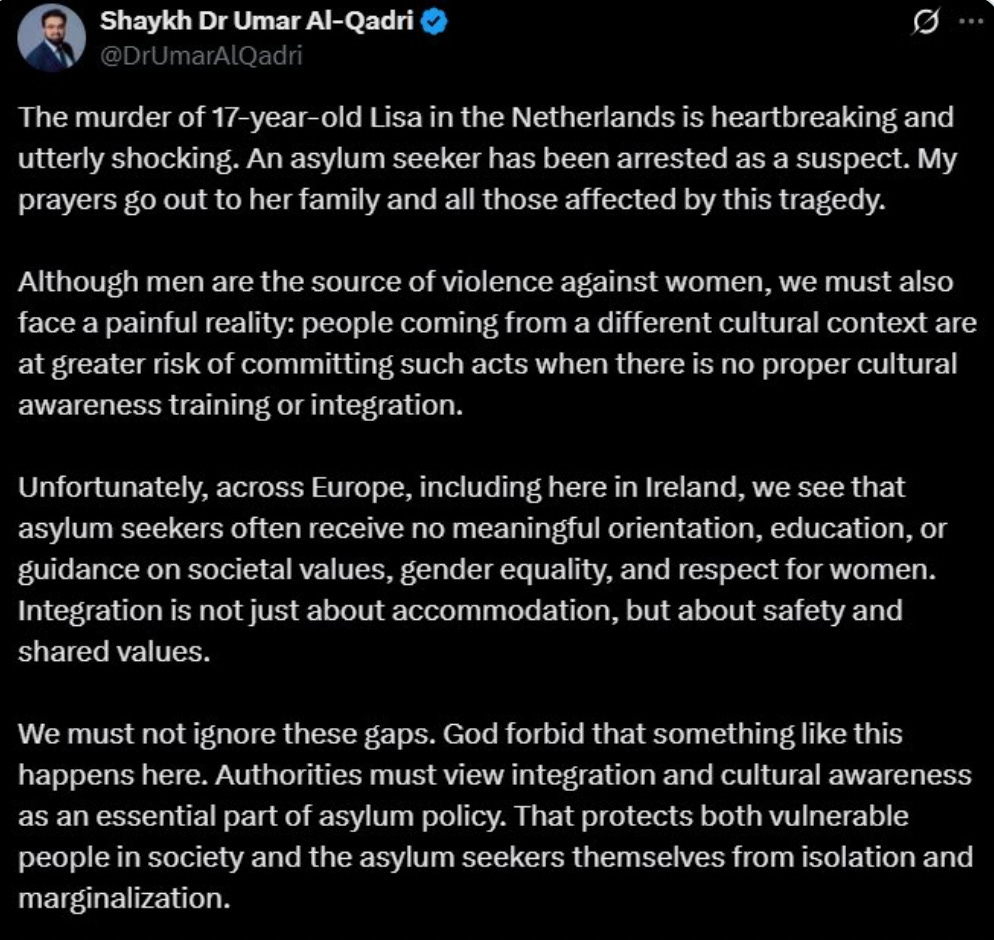

Meanwhile, the Chief Imam of Ireland would like you to know that it was sad that an asylum seeker raped a Dutch woman and later murdered a Dutch girl the other day, but society is also to blame for :::checks notes::: not telling him that rape and murder is wrong:

Poor marginalized asylum seeker. How was he to know it was wrong to rape women and murder them?

Somehow, I think the Irish, like many other Europeans, are in no mood to be talked to like this.

‘We Murder To Dissect’ — Wordsworth

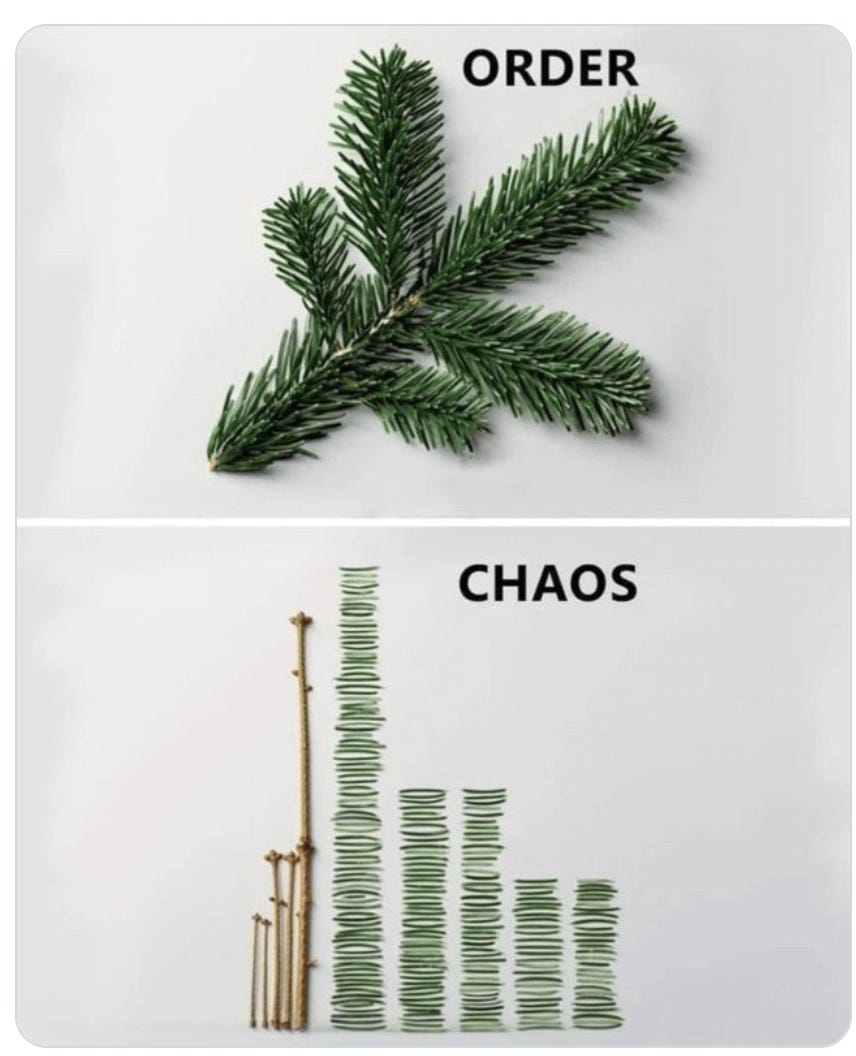

A great visual representation of the Medieval versus the Modern: